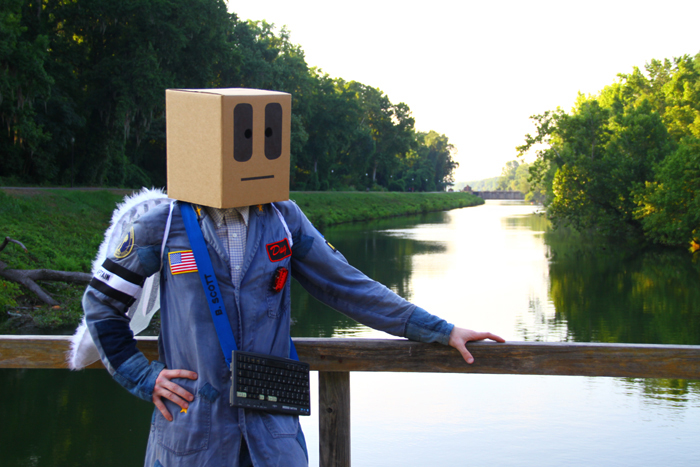

Slobot About Town CXXXVI:

|

|

Slobot goes to the Columbia Canal, pt. 01!

Slobot was bumbling along the Broad River...

when he stumbled upon a diminutive diversion dam.

Diminutive, at least, in comparison to its sizable stone neighbor.

That sizable stone neighbor, crowned with gears, marks one end of the ~3 mile long Columbia Canal.

On one end of the dam is a lock.

Lock keepers lived on site and collected tolls from passing boats and barges.

One quarterly report from 1827 listed 969 boats and 45,612 bales of cotton coming through the canal. |

The Columbia Canal and its locks were built in a part of the state that geologists call the Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line. |

| The Fall Line separates the hard, crystalline rock of the Piedmont from the softer, sedimentary rock of the Sandhills and the Coastal Plain. |

The change in geology creates a precipitous drop in elevation and, in turn, waterfalls, rapids, and shoals.

Such obstacles make it impossible for riverboats to navigate the Fall Line without having to portage.

Farmers working the Low Country of South Carolina had always found it quite easy to get their goods to market in Charleston. |

Farmers working the Up Country of South Carolina, however, were greatly hampered in their efforts to get their goods to Charleston. |

In a pre-train era, the most economical solution to the problem of transporting goods over great distances was the canal. |

Canals were all the rage in the 1820s. The Eerie, perhaps America's best known canal, would - for example - be completed in 1825. |

The original Columbia Canal was built in 1824 so that riverboats could navigate past the rapids found at the confluence of the Broad and Saluda Rivers. |

The 1824 canal had four lifting locks and one guard lock. Along each side of the canal was a towpath. Barges were pulled by tow lines connected to horses that walked the paths. Riverboats could also travel along the canal by using poles. |

The original canal served South Carolinians well for decades, but, by 1840, traffic and tolls had declined, and so the state of South Carolina pulled its funding. Things would only get worse with the arrival of the railroad. The railroad, which came to Columbia in 1824, rendered the canal obsolete as a means of moving commercial freight. |

The waters of the canal, however, were still of value. They, in fact, powered grist mills, and, during the Civil War, a gunpowder plant. |

| The power of the water was so proven during the Civil War that the canal would, in 1888, take on a new life as an industrial power source. The power generated here was used to power the Columbia Mill, the City of Columbia and the Columbia streetcar system. |

Two waterwheel-powered pump houses were added to the canal in 1906. Those pump houses would run until the 1970s. |

In their prime the pump houses would pump up to 7 million gallons of water a day from the Broad and Saluda Rivers. |

A new water treatment plant, the Columbia Canal Water Treatment Plant, was constructed just across the canal from the old pump houses. Today the plant draws its water supply directly from the canal and has a potential capacity of 100 million gallons per day. |

In 1983 a second water plant was opened on Lake Murray.

Though much of Columbia's water today comes from Lake Murray, the Columbia Canal is still vital to meeting Columbia's water needs. |

Columbia residents were reminded of the necessity of the Columbia Canal when it was breached by the rains of the October 2015 deluge. |

More on the events and aftermath of that deluge in the next episode, Slobot goes to the Columbia Canal, pt. 02! Slobot would like to thank the employees of the Riverfront Park, the City of Columbia, the Columbia Canal Water Treatment Plant and YOU! This episode is dedicated to Jason "The Love Commander" Leaphart (1977-2016). He was a founding member of Slobot and this web site. He took many (if not most) of the photos in this episode of Slobot About Town. |